UPDATE: This post was published on eWillys November 15, 2014. I don’t normally post whole articles, but there is a great deal of interesting information within it. I’m reposting this today because there is some additional information about Mr. Clement Miniger and his Auto-Lite company leading a syndicate to buyout John North Willys’ stock in 1929 (Learn more about Miniger And Willys Light here).

A variety of pre August 1946 CJ-2As in different colors waiting to be shipped from Willys-Overland’s Toledo plant.

This fascinating article was published in the August 1946 issue of Fortune magazine. It’s a LONG article that covers the history of Willys Overland Corporation from it’s bankruptcy in the early 1930s to it’s post-war market positioning. There is not much information specifically about jeeps, nor many jeeps photos. But, if you want to understand how the corporate structure evolved, it’s a good article.

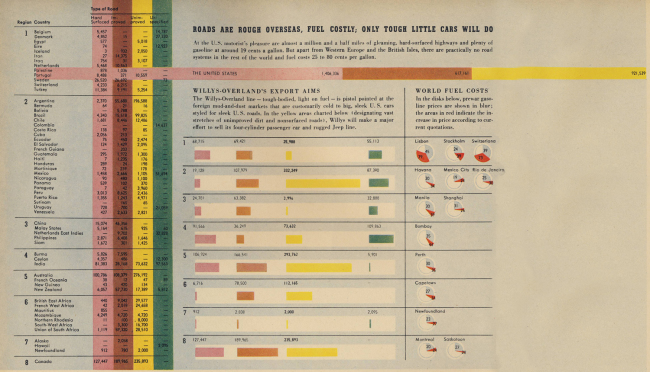

One particular chart published in the article was Willys’ research on paved roads. The company felt that jeeps would be very popular in outer countries, due both to the brand and the lack of paved roads. To meet that demand, Willys planned to export 25% of all jeeps.

WILLYS-OVERLAND

THIS JEEP-RIDING AUTO INDEPENDENT IS TAKING NEW LEASES ON LIFE AND ITS OWN REAL ESTATE • THE BOYS IN THE BACK ROOM ARE DOING FINE

ln the years between the depression and the second world war, the once great Willys-Overland Co. clung by its nails to a niche in the U.S. automobile market. Gamely, it tried to sell the public a mousy little car, with a tough, four-cylinder engine, which was the cheapest thing on the road to run. Itself battered into receivership and reorganization by the depression, Willys had the patently sensible idea that such a car, guaranteed to get people from here to there at a minimum expenditure for fuel and upkeep, would be a blessing to a hard-pressed public that had not been similarly served since the demise of the models T and A Ford. But the public was proud, if poor, and more conscious of the millinery than the engineering of a car. When it had to buy cheaply it found the used-car market much more tempting. During most of those years Willys’ production ranged below the break-even point. bln 1940, a mere 27,000 cars were built. Now Willys-Uverland is coming up for the postwar round with a product line still topped by a light passenger car-with a four or a six-cylinder engine, buyer’s choice. It will probably be as cheap to buy, give or take a few dollars, as any 1947 car on the market, and possibly less expensive to operate and support than any of its competitors. And though it will be considerably more stylish, inside and out, than the prewar Willys, it will have, at most, simple good looks rather than breath-taking beauty. If that were the whole story, one might wonder why some people think Willys-Overland is an exciting proposition among the auto independents today, and why some mighty big boys in the automobile industry appear to be sparring for position in the peculiar, complicated Willys-Overland hierarchy.

Unquestionably Willys has fresh charms. To name four:

1) The tough, four-cylinder motor that was the bread-and-butter item in the prewar Willys is the same motor that powered the Army Jeep, which became an international byword during the war. As the largest producer, by far, of the Jeep, Willys-Overland became the beneficiary of this enormous, war-born prestige (and also added a tidy sum to its treasury). Ten days after V-J day, Willys was in production on its civilian or Universal Jeep, of which it had sold around 28,000 by June 1, despite plant shutdowns totaling eighty-three days owing to strikes in suppliers’ plants.

2) Under way at its giant Toledo plant is a Jeep-inspired line of Willys utility vehicles including (a) an all-steel, all-purpose station wagon, (b) a sedan delivery truck, and (c) a low-weight, medium-duty truck with a combination four and two-wheel drive. All are powered by an improved four-cylinder Jeep engine and feature the Jeep snub nose and square fenders. All will be produced in 1946, and can be run through the same assembly line if necessary.

3) Because the rugged, lightweight vehicles in the Willys line are peculiarly suited to the exigencies of foreign motoring, in which the paucity of paved roads and the steep price of gasoline are forbidding factors, the company has decided to throw 25 per cent of its production into export. The development of a foreign market of such proportions is steadying to the seasonal economy of an automobile company. And Willys’ new top management is richly experienced in the export field.

4) Finally, many an economist, foreseeing an era of inflation, high taxes, and high gasoline costs, will agree that the hour in the oiiing is ripe for an automobile that places operating economy above fashion appeal. Willys is confident that its traditional economy car is, at last, accurately attuned to the times, and that its 1947 passenger model can bite into a solid and sustained market, both here and abroad.

For an automobile manufacturer to hew to a traditional policy of price and engineering over a long span of years is something of a distinction. Most companies, including Ford, have sedulously shifted with the competitive winds, the general tendency being to raise the levels of weight, speed, show, and, of course, the price of the product. In the case of Willys-Overland, moreover, it is remarkable that any recognizable tradition whatsoever has survived in view of the way the company has been buflfeted about financially and jounced under the weight of a management merry-go-round on which five separate presidents have ridden in the last ten years. It would almost seem that by some rite or alchemy the sprawling Toledo plant, with its acres of inanimate brick, mortar, and machinery, had been endowed with a soul or spirit of its own that mystically exerts an influence on the product–or, at any rate, enables the plant to respond nobly to the coaxings of a sympathetic engineer.

To weigh Willys’ new prospects, one has to look as closely at the personalities involved as at the product. And as with so many companies, you can’t guess where Willys is going until you’ve seen where it’s been. Modern Willys-Overland history begins on the day in 1929 when handsome, grandiloquent John North Willys sold out his common-stock holdings in the successful company he had put together some twenty years earlier (the market crash followed almost immediately). The deal represented no sly prescience on Willys’ part, however. The purchaser was a syndicate headed by his good friend, C. 0. Miniger of Electric Auto-Lite, who was mighty pleased to get a controlling interest in the company for a mere $21 million. And Willys’ real reason for getting quit was to accept an ambassadorship to Poland.

Under the depression’s impact, the company went straight to pieces, losing some $35 million in the years 1929 through 1932. In the fall of 1932, Mr. Willys was induced to return from Poland to try his skills at resuscitation. He threw $2 million of his own money into the company and sought bank credit for the balance of Willys-Overland’s working-capital deficit. On the day a Detroit bank was to loan him $1 million (February 14, 1933) the bank, along with every other bank in Detroit, closed its doors, and Willys-Overland went into receivership.

The prestidigitation that followed has to be watched closely.It was no journeyman performance. While the company bumped along in receivership, producing no more than a daily token of cars, and the bondholders and the cash creditors bitterly fought over a settlement of claims, George W. Ritter, a Toledo attorney who handled John Willys’ local legal affairs, began doodling with figures on his desk pad. He was not a nationally known corporation lawyer in any sense. George Ritter was. born down the line in Vermilion, Ohio, in 1886, attended Baldwin University and Cleveland Law School, and began practicing law in Sandusky in 1907. He came up to Toledo as a trial lawyer in 1913 and didn’t establish his own firm until 1917. Ward M. Canaday, whose agency handled Willys-Overland advertising, became his friend and client, and in 1925 Ritter became personal counsel for John Willys. He has disarmingly soft brown eyes, friendly Rotarian manners, and speaks rather slowly with a homespun Ohio accent.

George Ritter’s doodling was concerned with ways and means of getting the claims of the bondholders and the claims of the creditors into one hand-at thesmallest possible expenditure of cash money-in order to force a reorganization of the company, and then raise new money with which to run it. In the spring of 1935, Ritter showed these calculations to John Willys, who approved them and agreed to put up a substantial portion of the money required to swing the deal. Mr. Willys thereupon bounced oif to the Kentucky Derby, suffered a heart attack, and died the following August. But Ward Canaday, who had been looking over Ritter’s shoulder throughout the doodling, quickly jumped into the John Willys role, and the play was resumed. Mr. Canaday, onetime sprightly sales agent for the Hoosier Kitchen Cabinet Co., first bobbed up in the Willys picture as assistant advertising manager of the company in 1916.

He was shortly promoted to advertising manager but in 1921, when Willys was rocked by the postwar depression, he left to organize the United States Advertising Corp., taking the Willys account with him as a nucleus. (Willys still places its advertising through that corporation, now known as Canaday, Ewell & Thurber, Inc., of which Mr. Canaday owns 97.9 per cent.)

Canaday and Ritter then invited C. O. Miniger and the first Mrs. Willys, who owned considerable preferred stock in the company, to join them in the formation of Empire Securities, Inc., whose purpose was to buy up Willys-Overland bonds and outstanding claims. (J0hn’s other wife, whom he married in 1934, is not a part of this story.) There was $2 million in bonds out and Empire got 70 per cent of them for 70 cents on the dollar; there were unsecured claims of approximately $6 million outstanding and Empire bought up 97 per cent of them at 25 cents on the dollar. The total cost to Empire for the bonds and claims was $2,442,611, plus expenses. Only half of this money, however, was subscribed to Empire by Messrs. Canaday, Ritter, Miniger, and Mrs. Willys; the rest came from short-term bank loans to Empire Securities, Inc.

Empire now had completely palmed Willys-Overland.Through 77B of the bankruptcy law, Mr. Ritter’s reorganization scheme was pushed through- the courts in 1936. The interesting thing about the scheme was that it provided for the division of the old Willys-Overland Co. into two separate companies. One was Willys-Overland Motors, Inc., whose function was to go on making motorcars; the other was the Willys Real Estate Realization Corp., whose ostensible purpose was to gather up all the Willys real estate that would be a “burden” for the motor com-

pany to carry (including back taxes of $500,000) and eventually to liquidate or rent it.

Here it should perhaps be observed that by exercising various options under the plan, Empire traded in its bonds and claims for 1,400,000 shares of common stock in Willys-Overland, which represented control, and also secured the vast majority of common and preferred stock of the real-estate company.

Of Willys-Cverland Motors, Inc., it need only be said, at this moment, that it went out and raised $3,500,000 of new capital in a sale of stock underwritten by a syndicate headed by E. H. Rollins & Sons, Inc., of New York, and wrote up its appraised $1,290,000 worth of plant and equipment to a “going-concern” value of slightly under $10 million. With assets of $15 million it proceeded, in a modest way, to make cars. The immediate history of the real-estate company is more interesting, however.

At peak operation, in 1928, Willys-Overland turned out some 320,000 cars; the reorganized company was planning on producing only 70,000 cars a year. Therefore, Willys Real Estate Realization Corp. saw lit to take over almost the whole kit and caboodle of Willys-Overland’s vast fixed holdings. It took the giant six-story administration building (renting out two floors only to the motor company); it took 1,500,000 square feet of space from the company’s four-million-foot plant at Toledo; it took over the sizable Wilson foundry at Pontiac, Michigan, which makes all Willys’ castings; and it took over $1 million in cash that had been impounded in banks-proceeds from the sale of machinery that had been claimed by both bond-holders and creditors during their legal tussle.

With this cash item, plus the proceeds of various real-estate parcels sold oil (some to the U.S. Government), the real-estate company was able to retire the bulk of its preferred stock. Most of this retirement money was paid to Empire Securities, which then turned around and used the cash to liquidate the short-term loans it had originally made on organization. Eventually, Mr.Miniger and Mrs. Willys sold out their holdings in Empire to Empire. It is possible that this purchase, also, was made out of cash realized on the sale of real estate. Ultimately the real-estate company became a wholly owned subsidiary of Empire Securities, Inc., which in turn owned a clear controlling interest in the common stock of the motor company. How much actual cash it cost Messrs. Canaday and Ritter to come in at the tip of this inverted pyramid is not known. Some estimates put it as low as $500,000 for the pair of them. Mr. Canaday became Chairman of the Board of Willys-Overland Motors, Mr. Ritter’s firm its legal counsel.

For preliminary notation it might he mentioned that Willys-Overland Motors is now engaged in buying back from the real-estate company the principal “burdens” of which the latter relieved it in 1936 and 1937, i.e., the Wilson foundry, the administration building, the extra plant space, etc. For the volume of business Willys expects to do, it needs them. But more of that later.

Management–in flux

Meanwhile, the reorganized automobile company was having a grubby time. Though it started free of debt under the provisions of the ingenious Canaday-Ritter plan, it was relatively poor and unable to strike out in a bold way. Rugged old David Wilson, former head of the foundry, whose guts and shrewdness had kept the shop alive during the days of receivership, was President, and a mighty unhappy one under the heel of the white-collar hierarchy. Finally, in 1939, after a spectacular Board meeting during which Wilson’s formidable forefinger emphasized a point with such vigor that the Board Chairman was reportedly precipitated into a nearby wastebasket, old-timer Wilson went back to retirement in Pontiac, Michigan. He was succeeded by Joseph Frazer from the Chrysler Corp. The Directors felt the sales organization needed shoring up and Joe Frazer was one of the industry’s crack sales executives.

On the engineering side, Wlllys Overland ha ma e a strike in 1938 when it secured the services of Delmar G. (Barney) Roos, whose blend of idealism and practicality makes him a handy guy to have around a shop, as both a dreamer and a doer. Roos’s frank, arresting features, outthrust from a wrestler’s neck and shoulders, are a familiar sight at meetings of the Society of Automotive Engineers of which he was once president, and his stubby fingers on the drawing board have contributed a great deal to the complexion of the modern motorcar.

He began his career with big cars-the Locomobile, the Pierce-Arrow, the Marmon. In 1926 he joined Studebaker as chief engineer and there developed an entirely new line of cars and trucks, some of which are still in production. Then he went to England as consultant to Rootes Ltd.-whose subsidiaries include Humber, Sunbeam, and others-and became a whole-souled devotee of the small, light car. “Not the toy cars you need a shoehorn to get into,” he assures you, “but a car with less steel and spinach that gets back to the fundamentals of transportation. This nation could cut its gasoline bill in half and still have adequate, comfortable transportation.”

Returning to the U.S. in 1938, Roos bypassed Big Three offers to go with Willys-Overland because “it was the only company building anything like what I believed to be the future volume car of the U.S.” It was certainly not the then current volume car-in the years 1937-4-1, Willys averaged only 35,000 cars a year–but there were extenuating circumstances. Roos was never able to build a Willys car from scratch. His predecessors had made extensive commitments for stampings and parts and, like a good housewife, Barney had to use them up. By remarkable improvising, he got off the line a Willys Americar that was nothing to be ashamed of. The Frazer-Roos team was just beginning to click in passenger-car manufacture when the war came, and with it a sharp turn in Willys-Overland’s destiny.

THE JEEP IS BORN

Nobody, not even in its darkest days, ever accused Willys-Overland Co. of lacking sheer manufacturing skill. A home-town outfit, it has always maintained a solid core of workmen who knew how to tackle machine problems. Therefore, when the Army, though reluctant at first to deal with small producers, gave Willys a crack at scout-car design the company responded smartly. Early in the negotiations an Army officer whispered to Roos, “Above all, Barney, make it tough,” and so Barney piled in all the power he could muster. He knew that in the final showdown he could shave the weight to specifications. With Willys-Overland that is the specialty of the house. Getting the Jeep contract was a plume in Willys’ cap, and along with other government contracts for naval hoists, 155-mm. shells, Corsair plane-wing parts, etc., it brought a substantial boost to the company’s working capital. In fiscal 1941 earnings went from a red $800,000 to a black $800,000; in 1942 its profits were $1,265,000; in 1943 they were $3 million; at the end of 1944 the company’s assets had billowed to $73 million, with profits of $4 million and a working capital of $14 million.

Signs of undersurface unrest were not totally absent during the war years, however. In 1943, Mr. Frazer exercised his options on 75,000 shares of stock, which netted him about $200,000, and quit the presidency of the company. Mr. Frazer’s and Mr. Canaday’s aims and ideas were not altogether compatible.

Midway in the war Willys-Overland began pointing toward its postwar livelihood. With the war-production lines well grooved, Barney Roos had time to do some creative thinking and to dust off and freshen up the passenger-car program he and Joe Frazer had nursed along in earlier days. Then, in the spring of 1944, Ward Canaday induced Charles Sorensen to quit the Florida beach where he had been resting since his rather abrupt retirement as Henry Ford’s right arm, and to take on the presidency of Willys-Overland (Canaday himself had been the interim President). Part of the inducement was a contractual agreement to pay Mr. Sorensen $52,000 a year for ten years whether he lived or died, as well as an option to purchase 100,000 shares of Willys-Overland common stock at $3 per share (then selling at $12.50 a share, recently at $26.75). From Mr. Sorensen’s view, doubtless, the opportunity to swing one more big automobile job was the greater lure. He went into the reconversion program with considerable vigor. At Ford Motor Co., Sorensen had built Army Jeeps from Willys-Overland blueprints, and his admiration for the vehicle was high. He drove on the civilian-Jeep program and had it ready for the assembly line ten days after V-J day. His thinking contributed enormously to the new Willys utility line, and his rough powers of persuasion clinched its acceptance by a skeptical Board. At sixty-four, “Castlron Charlie” is hard and brown, and full of beans.

Naturally the industry thought that Charlie Sorensen would lead the Willys team, and the products that were largely of his building, into the great race coming up in the automobile world. Therefore the announcement in January of this year that James D. Mooney, formerly of General Motors, had taken over the presidency and board chairmanship of Willys-Overland was something of a shocker. Not that the sixty-two-year-old Mooney, an ‘engineer by profession, a C.M. Director and top executive, and fresh from a wartime captaincy in the U.S. Navy, was anything less than a good catch for any company in the business. But in the circumstances connoisseurs of Willys-Overland history wondered if another President had come a cropper in the Board room. Impressions of this kind were strengthened when it was observed that Mr. Sorensen was more often to be found at his Florida retreat than in his Toledo office.

Willys-Overland, on its part, accounts for the changes in a most logical way. It was a part of Mr. Sorensen’s employment contract that at such time as he might deem appropriate another man would be elected President, with Sorensen moving on to fill an ofiice to be created. As vice chairman of the Board, he continues in a consultative and advisory capacity to Mr. Mooney.

POLICY — BY MOONEY

The new Willys Chairman and President is a ruddy, hefty Irishman with a scholarly bent for philosophy and economics. Though business is fun to him he has never been known to play it for marbles. At Toledo he looks with vast enthusiasm on the materials he has been given to work with. In the welding of his policies and personality with the Willys tradition and product, no seams are visible to the naked eye.

“Our philosophy,” says Mr. Mooney, “begins with a platitude: we have to pay for the war. Money, credit, and prices will all express that in one way or another in the next few years. You can’t devitalize a country’s industry for six years-four years of war and two of active preparation for war-and not pay for it some way. For a while we’ll all be poor. We’ll have a complexion of being richer-in paper dollars-but with taxes and higher prices we’ll actually be getting along with very much less.

“At this very moment,” Mooney acknowledges, “price is no object to the public, but we’re shaping our programs for the larger economic picture, for what you might call the middle-term pull between the time when the first gush of spending exhausts itself and the point where there is a more general production and distribution of luxury goods. lt’s during that middle period that we feel there’ll be a broad opening for this company with its appealing utility line.”

“Our program,” he summarizes, “is in line with the Willys tradition. Before the war, Willys always produced a lighter-weight, smaller-capacity automobile. During the war-in a short period-we established the tradition of the Jeep. By keeping both, by capitalizing fully on our fame, and by maintaining our realistic relationship to the economics of the country, we’ll have a sound and successful program.”

PRODUCT — REFURBISHED

The best-reasoned programs, of course, have their elements of expediency, improvisation, and opportunism, and the Willys-Overland line is no exception. Indeed, it is a rather remarkable example of fast footwork and invention out of necessity.

THE UNIVERSAL JEEP. With all the world engaged in a barefaced love affair with the U.S. Army Jeep, it would have been unusual if Willys-Overland, its builder, failed to give some thought to a postwar civilian adaptation of the vehicle. The company began experimenting in that direction a year and a half before the war was over, and most engineers will concede that the Universal Jeep is sturdier, more usable, and generally superior to the Army Jeep. It is a small tractor, light truck, and passenger car combined. Equipped with air compressors, electric generators, power take-off, welding arc, belt, drawbar, etc., it can do the work of a small farm tractor, handle all the general farm power problems, and haul passengers at highway speeds.

The Jeep is a unique vehicle that deserves a longer life than it probably will enjoy. As a fad it is selling even in passenger-car markets now, though by such standards it is uncomfortable and expensive. Generically, it is a piece of machinery and has to be sold as such. ln the long run, Willys’ Jeep sales (except for export) will depend largely on the ability of its dealers to develop the techniques that sell tractors and machinery. Unless automobile salesmen have changed a lot, the Jeep is a worthy piece of business that may pass away by default. Meanwhile, the Jeep is a source of inspiration and profit to Willys. If supplies are not restricted, the company expects to sell 70,000 of them this year, and slightly less than half that number in 1947. Even when the Jeep carries the plant’s entire overhead, its break-even point is 4,500 units a month-54,000 a year.

THE JEEP STATION WAGON. Willys-Overland emerged from the war with no ready source for heavy-press passenger-car body stampings. Though unable to start its new passenger model, it nevertheless wisely shunned re-identification with the old one. In searching for a quick entry into the passenger-car field, it lit on the idea of a station wagon. There was no reason Why the Jeep axle, wheel, transmission, etc., couldn’t be used for such a model, and by designing the simplest of stampings the company could readily find facilities for their supply. So the company went ahead and tooled for its proposed postwar passenger-car chassis, and then built a station wagon on it. The result, however, was something quite distinct from the conventional station wagon, which is basically a wooden sedan. The Willys station wagon is an all-steel job that rides with close to passenger-car comfort. lt carries seven passengers on seats that are easily removable, thus permitting the vehicle to be effortlessly converted to a truck or general-purpose car. It is highly maneuverable on its l04-inch wheel base, and its four-cylinder engine is cheap to feed. Finally, it is to be priced for “people who never saw a station wagon up close.”

With its jaunty Jeep bonnet, square fenders, and sleek steel body, the Willys wagon is a fetching piece. But the significance lies in the attempt it represents to mass-produce what has heretofore been a luxury vehicle. Boldly, it aims to cut itself a slice of both the station-wagon and the passenger-car business of Willys’ competitors. The gamble is that it may fall dismally between the two stools. But it is not an overcostly gamble, at that, because the Jeep station wagon shares its production expense with the other members of the utility family.

THE SEDAN DELIVERY TRUCK. The stampings on the Jeep station wagon are such that, merely by eliminating the windows, Willys can make another product without extra cost -the sedan delivery truck. It has the same Jeep engine, front end, wheel base, chassis, etc., as the station wagon and can ride on the same assembly line. The delivery wagon will probably be cheap to buy, cheap to operate, and it looks like what it is–a functional, lightweight, commercial vehicle.

THE MEDIUM-DUTY TRUCK. Willys’ wartime experience taught it a lot about four-wheel drives and out of this knowledge it has built what it believes is the first light four-wheel-d1°ive truck in history. It can bite into almost any kind of road in any kind of weather and Willys will aim it at farmers, dairymen, and others who use light trucks but encounter a lot of off-the-road haulage. It will have approximately a one-ton pay-load capacity. Moreover, it is designed so that the four-wheel drive is optional: a flip of a gear switches it to a two-wheel drive at will (Willys also sells a two-wheel-drive truck). Barney Roos’s boys are particularly proud of this job. This is the first time anyone has ever put a two-wheel and a four-wheel drive on the same chassis.

From its utility offering Willys-Overland hopes to draw almost 50 per cent of its volume when its business is stabilized. At this point, cost estimates aren’t available but the line obviously has a high standardization of body and parts and will require a minimum of expenditure from year to year for redesigning. Tooling costs should be written off pretty quickly. The line seems excellent for export and is not seasonal. lt is really the basis of Willys-Overland economy.

THE PASSENGER CAR. Conservative is the word for the appearance of the Willys-Overland 1947 passenger car, and the company doesn’t care if you say it out loud because that is the professed policy of the firm. There is a slight accent of asperity in Jim Mooney’s soft, smooth voice when he says, “We’ll not get out a trick or miracle car. It will be stylish without pretending to be fashionable. We think a car is too expensive an item to follow ever changing fashions. Most other products of comparable cost are, in fact, conservative and relatively stable in design. The average family can’t take it very long if you go on creating false obsolescence in their cars.”

The specifications of Willys’ passenger cars have now been finally determined but the appearance of the front is still undergoing change. The ultimate design accepted will be the “face” of Willys-Overland for years to come, and all the models that follow will be recognizable lineal descendants of it. The Willys will be a small standard-tread car-under 2,500 pounds-but its engineers will endeavor to give it two qualities that are devilishly difficult to incorporate in a car of that size: (1) easy riding, and (2) comfortable seating. On point No. 1, Barney Roos thinks he has solved the problem by adapting independent wheel suspension to all four wheels instead of the customary front two, yet maintaining road stability of the car. This has been done by combining a variation of so-called “knee action” on the front with the German-type swinging axle on the rear. On the second point, the problem has been attacked by planning the front seat to hold three people comfortably, the back seat two. Also the seats have been raised to permit improved posture for riders; but because independent suspension has dropped the floor down, no adjustment will have to be made in the ceiling of the car. The company has also out deeply under the front seat to allow long legs maximum freedom.

The new Willys sedan will be a two-door job because its 104-inch Wheel base is too short for four doors. The doors will be unusually wide, and a pivot arrangement under the right front seat permits easy entry and egress. Also, by making a two-door sedan Willys can produce a two-door coupe (as well as a convertible to tone up the line) from the same stampings; altogether, the saving averages $75 per car.

In one respect Willys will break sharply with its passenger-car tradition: a six-cylinder motor will be used, though a four-cylinder car will be turned out too, largely for export purposes. But Willys will have the smallest six-cylinder engine yet seen in an American car-only l4l8 cubic inches and trimmed to within five pounds of the weight of its four-cylinder engine. The Willys-Overland Won’t be the fastest car on the road or have the best pickup, but it will have a top speed of eighty miles per hour, and its makers are confident that no car in its class will excel it in economy of fuel and upkeep.

Willys will have plenty of competition in the passenger-car field, however. Big Three companies have already announced plans to produce lightweight cars and at the outset some of them will undoubtedly be priced as low as Willys’. But the Toledo company figures that if it can establish a beachhead in the economy-car field, it can probably hold its own when price becomes a paramount issue. It will be observed that Willys-Oven land is banking strongly on the accuracy of its economic forecast. Its chips are down on cheap cars. At present, it is planning no entry in the medium-priced field.

POINTING FOR EXPORT

For an independent, Willys-Overland is gunning for foreign business in a big way; indeed, with regard to export it is as daring and as knowing as any of the Big Three. Even when its fortunes were at low ebb, Willys had a relatively high export quota-17 per cent-and under its new program the allotment will be pushed to 25 per cent, regardless of the range of local demand. There are several sound reasons for this policy. Foremost is the fact that the company’s utility cars, along with the passenger line, by virtue of structural toughness and economy of operation are practically custom-made for the crude roads and expensively priced gasoline of foreign countries (see chart on page 84). And in the automobile business an export outlet is something more than an additional market: it furnishes a desirable load factor for the plant, which is otherwise subject to the extremes of the seasonal cycle.

Whatever a stout foreign business may be worth to a company like Willys-Overland, its new management can be expected to make the most of it. As the head of General Motors Overseas for many years, Jim Mooney on his record is presumed to know the score as well as any man in the business. The nucleus of a sparkling overseas organization, including men recruited from corresponding posts in the aggressive General Motors organization, can already be found at Toledo desks. (In contrast to G.M., however, Willys plans to cooperate with local capital and management in the eventual establishment of assembly plants abroad.) Heading the Willys-Overland distribution setup, both foreign and domestic, is Arthur J. Wieland, after twenty-two years in responsible G.M. export-division posts. If anything, Willys-Overland is a bit top-heavy in sales talent of this type.

PAINTING A GRAY ELEPHANT

If Willys-Overland is talking big these days it has the background for bigness, as independent automobile companies are measured. If old John Willys’ giant plant was a burden back in 1933, it’s a blessing now. Compared with Willow Run, Willys’ Toledo plant is grimy and dingy, and bending here and there at the beams. But compared with Willow Run, Toledo has a potentiality of 4,300,000 square feet as against 3,700,000 square feet for the Kaiser-Frazer workshop. And the Willys plant was built to make small automobiles, not B-24 bombers, a very significant difference in the opinion of Willys’ Charles Sorensen, builder of Willow Run.

The Willys assembly line, minus much of the timesaving machinery the plant owns today, once ran 320,000 cars in a year without trouble, and manager Bill Paris has no fears for his capacity. Where it used to take eighteen days to run a body through from scratch, the trick is now done in forty-eight hours. So, as Willys’ production expands, the plant problem will be a relatively simple one of handling, not of space. The present Jeep assembly line could accommodate the entire utility run, if necessary, with the addition of two shifts, but a parallel line is now being built to handle the new passenger car, the station wagon, and the sedan delivery. The truck will be run on the Jeep line.

Willys-Overland already makes the major part of its product in its own shop. The motor block and cylinder head come in from its Wilson subsidiary in Pontiac but are machined in Toledo. Willys buys some standard parts like pistons, but makes its own crankshafts, connecting rods, tubings, and small stampings. In a matter of time it will stamp all its own bodies.

To date, Willys’ sole labor troubles of any account have been restricted to its sufferings from suppliers’ labor troubles. The plant hasn’t had a major strike since 1923.

RIGHT HAND, LEFT HAND

Looking back on Willys-Overland’s past, and observing the company’s technical resourcefulness, its impressive physical capacity, and its ability to survive on a “wear it out, use it up, make it do” style of operation, it would seem that there has never been anything wrong with the company that a sufficiency of cash money wouldn’t cure. Church-mouse poor since its reorganization, the company went into its ambitious war program with less than $2 million of working capital. Even at war’s end, it had less than $20 million in funds available for equipment and expansion. Perhaps its current refinancing, an offering of preferred and common shares to current stockholders that is to recruit $21 million in new money, will supply the answer.

The new financing operation returns the story to the Willys Real Estate Realization Corp., and its parent, Empire Securities, Inc., wholly owned by Ward Canaday, George W. Ritter, and, now, James D. Mooney, who acquired 9.77 per cent of Empire’s stock when he came over to Willys from G.M. Out of the $21 million Willys-Overland stockholders will pony up, roughly $6 million will be turned over to the real-estate company for the purchase of the Wilson foundry (at $3,700,000) and the other buildings. The balance will be spent for the new assembly-line machinery, and for various jigs, Welders, presses, etc., needed to implement the new production program.

The repurchase of these properties by Willys can, of course, be defended on wholly logical grounds. The company needs ownership of the Wilson foundry for the same reasons that prompted John Willys to buy it from Dave Wilson in the first place, back in 1919. And in view of a production schedule that calls for at least 300,000 units to be made in 1948, Willys needs the extra plant space it is rebuying. Though a stockholder might well squirm at the thought of using working capital now for such a purpose, even with the additions the Willys-Overland plant account of $17 million will remain a modest item in relation to the company’s total worth and projected operations. To be sure, the Canaday-Ritter-Mooney real-estate company profits $2,900,000 by the sale of the foundry and $1,500,000 by the sale of the supplementary space, but the inherent worth of the properties is considerably in excess of the sale price.

lt might be said that the transaction is not wrong in itself, but it points up what has been wrong or constrictive with Willys-Overland these many years as a manufacturing enterprise. It is the situation by which Mr. Canaday, an advertising man, and Mr. Ritter, an attorney, in the process of saving the automobile company in 1936 and splitting it up as they did, simultaneously acquired control of two entities that could conceivably find themselves in conflict over an issue facing either of the corporations. For example, it was once Mr. Ritter’s sad duty, as representative of the real-estate company, to inform the Directors of Willys-Overland Motors that a very fine offer to buy the Wilson foundry had been received from an outside source, and that unless Willys-Overland was prepared to act, Willys Real Estate Realization felt compelled to sell. Mr. Ritter is also a Director and counsel of Willys-Overland Motors. As Director, of course, he would disqualify himself from voting on the proposition. But, as counsel, what position would he take? Or if he declined, as an interested party, to take a position, where would Willys-Overland go for counsel?

Such contretemps are inherent in the Willys setup. This is doubtless the main source of the irritation that has developed, off and on, between the men who make the automobiles and the men who control the shares. Barring a change in such control, the condition could be assuaged or eliminated only by an increasing community of interest between a holder of shares in Willys-Overland and a holder of shares in Empire Securities; that interest, in turn, should be solely concerned with the successful prosecution of an automobile-manufacturing business.

Accordingly, the liquidation of Empire Securities’ real-estate holdings, however much it might cost Willys-Overland, is perhaps the best investment the motor company could make for its future in more ways than one. With Empire Securities, lnc., eventually stripped down to a holding company for Willys-Overland shares, nothing on the horizon should be more attractive than the opportunity to make automobiles for profit. That goes for Mr. Mooney. That goes for Mr. Canaday.

I especially love this:

“The Jeep is a unique vehicle that deserves a longer life than it probably will enjoy. …. Unless automobile salesmen have changed a lot, the Jeep is a worthy piece of business that may pass away by default. ”

I wonder what the author would say about the fact that a successor to the original CJ is still selling in volume nearly 60 years after he wrote those words?

I also found it interesting that the author referred to pre-war station wagons as vehicles for the rich. I suspect that he was confused. While pre-war woody wagons were sometimes the utility vehicles of the rich, many were used for their original purpose: taxiing people and luggage from the train station. They weren’t the top of the line in any automaker’s passenger car lines. That spot was normally taken by the 7 passenger sedan or town car. After the war, the woody wagon (and sedan) became a fashion accessory. Often, however, the wood was cosmetic or largely cosmetic (as in the Packard and Buick lines), not structural (as in the original pre-war cars). The Willys tin woodies were a hat tip to the fashion, but certainly not the comfort, of it’s competitor’s vehicles.

While the pre war station wagon bodies were mostly made of wood, they may not have been the cars for the rich necessarily, but they were almost always the most expensive cars in the production line whether they were Fords, Chevys, Chryslers or Packards.

I find it interesting to see the name of the vast holding company that did a lot of Willys financing and real estate holdings over the years. Empire: I always wondered why the tractor made by Willys and for the most part exported, was called the Empire. Now I have a clue!

Thanks Dave for posting this interesting look into Willys Overland history.

Have a safe trip to NYC.

Colin — Here’s the history summary I wrote about Empire Securities and Empire Tractors with Carl Hering’s help. Based on the Fortune article’s history, I’ll probably need to update it:

http://www.ewillys.com/2014/05/27/empire-tractors-the-tractor-clothed-jeep/

It’s obvious that back then no one could envision a 4X4 / off-road market for jeeps. The early advertising did point out that hunters and fishermen could go places with the jeep that wouldn’t have been easy to get to without them, but it almost seemed like they throwing that idea out there in the hopes that a few more might be sold that way.

THE BEST PART OF THE ARTICLE WAS THE PIC OF THE ” 7TH ” SEAT — VERY ELUSIVE SEAT IT IS …

Fascinating. Thanks for posting, Dave. Happy Thanksgiving to

you and Ann.